You’re getting hitched in sunny Florida and you’re wondering what to include in your prenup so it holds up against all of the sunshine, beautiful beaches, and Miami nights. Here is some information you need to know about Florida prenups, including some terminology you’ll want to know and links to the official state laws.

A prenuptial agreement (referred to as a premarital agreement in Florida) is a private contract between two people who plan to marry. Florida refers to their statute as the Uniform Premarital Agreement Act. A premarital agreement is drafted prior to marriage and details the financial rights and ownership of certain property both during the marriage and upon divorce or separation. Premarital agreements can also address what happens in the event of death. In Florida, a premarital agreement is not in effect until the marriage takes place.

Florida adopted the Uniform Premarital Agreement Act (UPAA) in 2007. The UPAA lays out uniform rules to help courts determine whether or not a prenuptial agreement should be enforced. You can read all about the Uniform Premarital Agreement Act here.

Want a little history lesson? In 1972, in the case of Posner v. Posner, 257 So. 2d 530 (Fla. 1972), the Florida Supreme Court upheld a prenuptial agreement containing spousal support provisions- this was previously a concept that had been deemed void as against public policy. In 1983, the Uniform Premarital Agreement Act (UPAA) was drafted in reaction to growing concern over the lack of uniformity in prenuptial agreements, as well as to validity and enforcement of these contracts. The demand for premarital agreements was steadily increasing. In 2007, Florida adopted parts of the UPAA, thereafter creating Florida’s own UPAA.

The Florida Uniform Premarital Agreement Act dictates what can be included in a valid Florida premarital agreement. Per the Act, the definition of a premarital agreement is:

“Premarital agreement” means an agreement between prospective spouses made in contemplation of marriage and to be effective upon marriage.”

Per the Act, you may contract with respect to the following:

Parties to a premarital agreement may contract with respect to:

1. The rights and obligations of each of the parties in any of the property of either or both of them whenever and wherever acquired or located;

2. The right to buy, sell, use, transfer, exchange, abandon, lease, consume, expend, assign, create a security interest in, mortgage, encumber, dispose of, or otherwise manage and control property;

3. The disposition of property upon separation, marital dissolution, death, or the occurrence or nonoccurrence of any other event;

4. The establishment, modification, waiver, or elimination of spousal support;

5. The making of a will, trust, or other arrangement to carry out the provisions of the agreement;

6. The ownership rights in and disposition of the death benefit from a life insurance policy;

7. The choice of law governing the construction of the agreement; and

8. Any other matter, including their personal rights and obligations, not in violation of either the public policy of this state or a law imposing a criminal penalty.

(b) The right of a child to support may not be adversely affected by a premarital agreement.

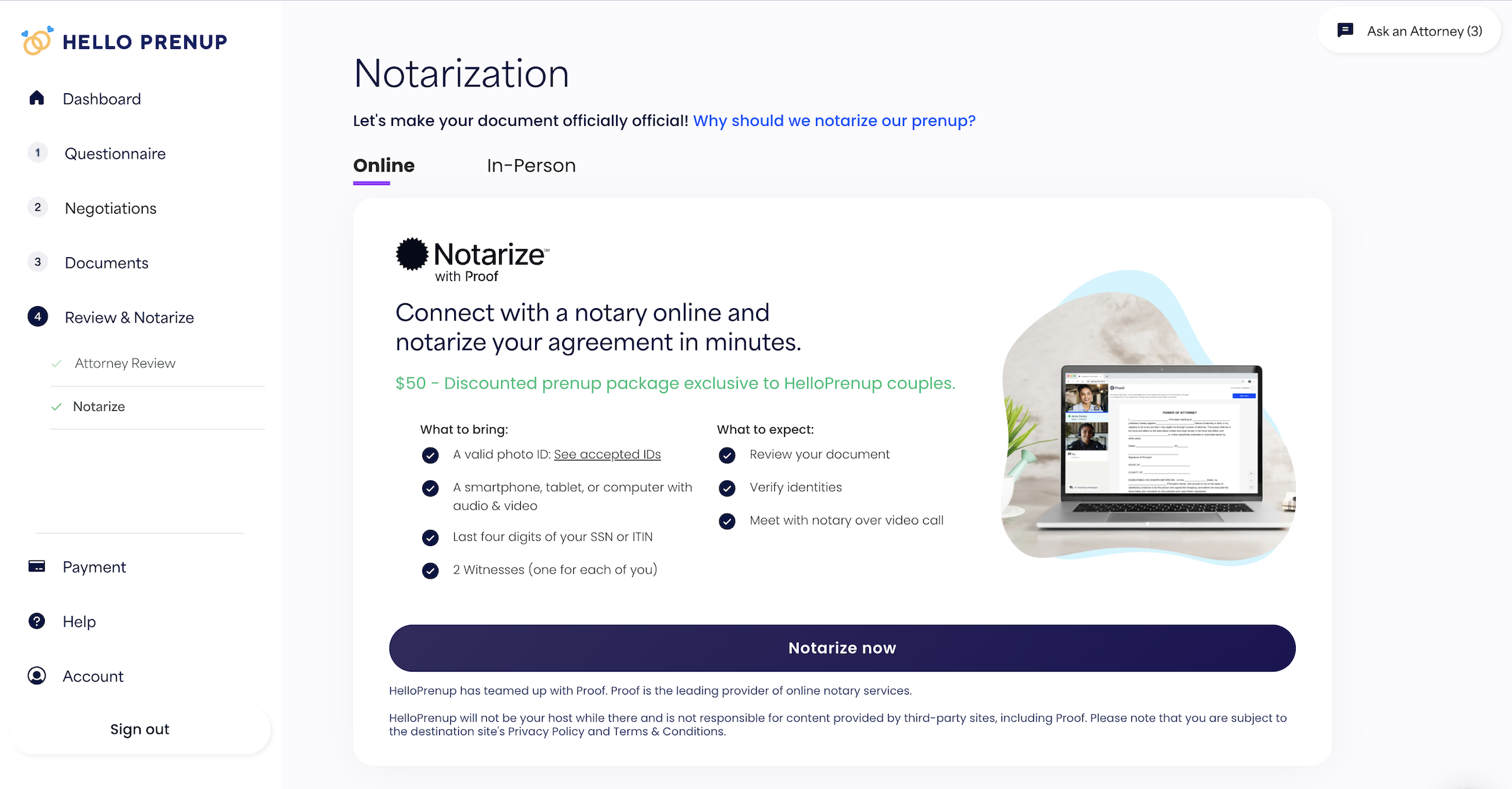

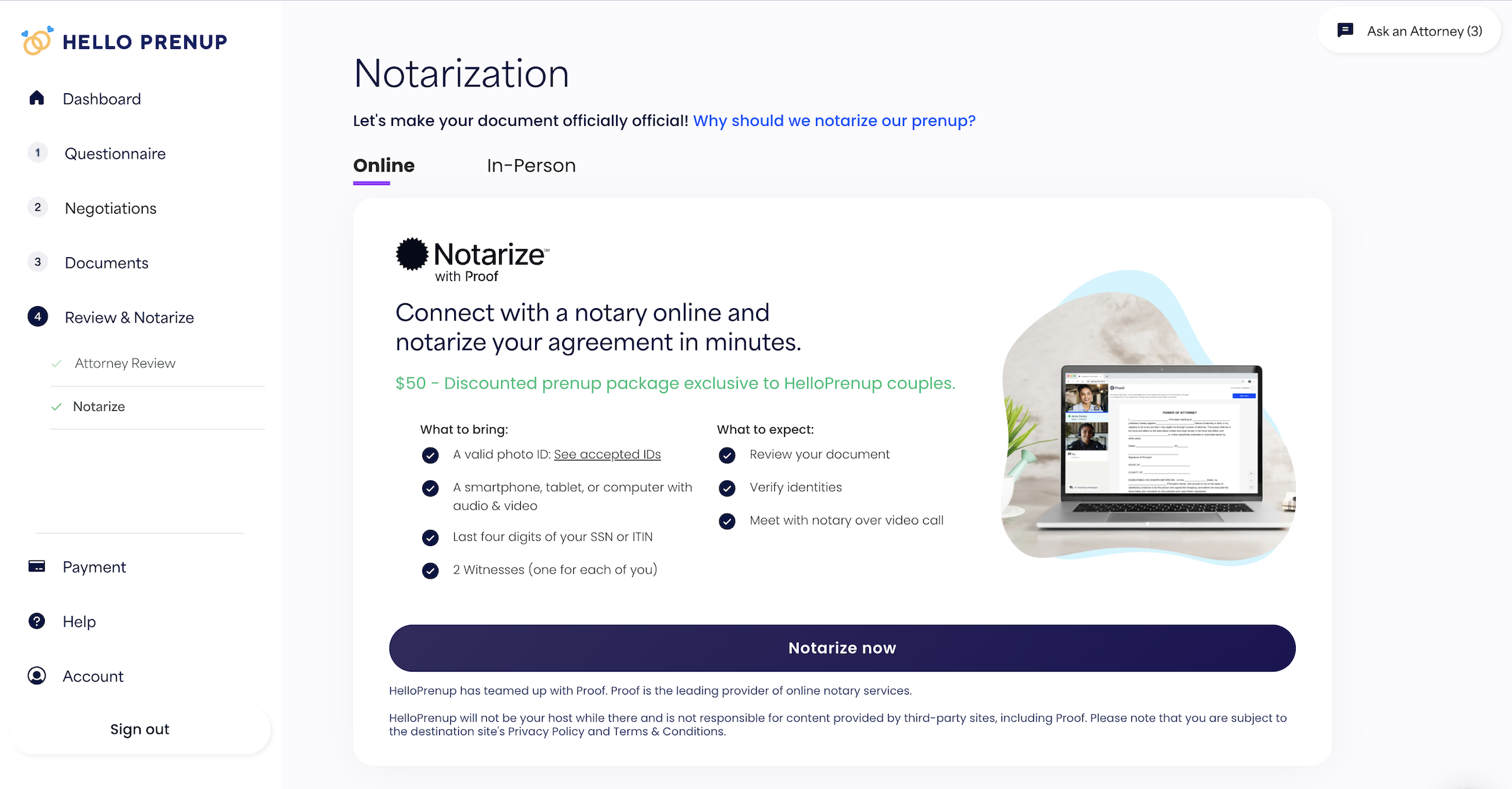

Add-on Florida notarization available now:Get your prenup notarized online with our exclusive partnership with Proof (formerly Notarize.com)

Now you can create your prenuptial agreement, collaborate on terms with your partner & optional attorneys, then notarize your prenup—all from your couch. The only thing we can’t do? Get married for you.

If you purchase Attorney Representation with your prenup, Notarization is included.

*Two witnesses will be provided as needed to notarize your prenup in Florida.

Official term for jointly owned property

In Florida, marital property is divided equitably in a divorce (but not always equally). States are considered to follow a community property theory or an equitable division theory. Florida is an equitable division state.

According to the Florida statute, Marital Assets and Liabilities can include:

“Marital assets and liabilities” include:

a. Assets acquired and liabilities incurred during the marriage, individually by either spouse or jointly by them.

b. The enhancement in value and appreciation of nonmarital assets resulting from the efforts of either party during the marriage or from the contribution to or expenditure thereon of marital funds or other forms of marital assets, or both.

c. The paydown of principal of a note and mortgage secured by nonmarital real property and a portion of any passive appreciation in the property, if the note and mortgage secured by the property are paid down from marital funds during the marriage. The portion of passive appreciation in the property characterized as marital and subject to equitable distribution is determined by multiplying a coverture fraction by the passive appreciation in the property during the marriage.

Official term for independently owned property

According to the Florida family law statute, “Nonmarital assets and liabilities” include:

1. Assets acquired and liabilities incurred by either party prior to the marriage, and assets acquired and liabilities incurred in exchange for such assets and liabilities;

2. Assets acquired separately by either party by noninterspousal gift, bequest, devise, or descent, and assets acquired in exchange for such assets;

3. All income derived from nonmarital assets during the marriage unless the income was treated, used, or relied upon by the parties as a marital asset;

4. Assets and liabilities excluded from marital assets and liabilities by valid written agreement of the parties, and assets acquired and liabilities incurred in exchange for such assets and liabilities; and

5. Any liability incurred by forgery or unauthorized signature of one spouse signing the name of the other spouse. Any such liability shall be a nonmarital liability only of the party having committed the forgery or having affixed the unauthorized signature. In determining an award of attorney’s fees and costs pursuant to s. 61.16, the court may consider forgery or an unauthorized signature by a party and may make a separate award for attorney’s fees and costs occasioned by the forgery or unauthorized signature. This subparagraph does not apply to any forged or unauthorized signature that was subsequently ratified by the other spouse.

Alimony Upon Divorce

Here is the fine print from the Florida statute itself:

61.08 Alimony.—

(1) In a proceeding for dissolution of marriage, the court may grant alimony to either party, which alimony may be bridge-the-gap, rehabilitative, durational, or permanent in nature or any combination of these forms of alimony. In any award of alimony, the court may order periodic payments or payments in lump sum or both. The court may consider the adultery of either spouse and the circumstances thereof in determining the amount of alimony, if any, to be awarded. In all dissolution actions, the court shall include findings of fact relative to the factors enumerated in subsection (2) supporting an award or denial of alimony.

(2) In determining whether to award alimony or maintenance, the court shall first make a specific factual determination as to whether either party has an actual need for alimony or maintenance and whether either party has the ability to pay alimony or maintenance. If the court finds that a party has a need for alimony or maintenance and that the other party has the ability to pay alimony or maintenance, then in determining the proper type and amount of alimony or maintenance under subsections (5)-(8), the court shall consider all relevant factors, including, but not limited to:

(a) The standard of living established during the marriage.

(b) The duration of the marriage.

(c) The age and the physical and emotional condition of each party.

(d) The financial resources of each party, including the nonmarital and the marital assets and liabilities distributed to each.

(e) The earning capacities, educational levels, vocational skills, and employability of the parties and, when applicable, the time necessary for either party to acquire sufficient education or training to enable such party to find appropriate employment.

(f) The contribution of each party to the marriage, including, but not limited to, services rendered in homemaking, child care, education, and career building of the other party.

(g) The responsibilities each party will have with regard to any minor children they have in common.

(h) The tax treatment and consequences to both parties of any alimony award, including the designation of all or a portion of the payment as a nontaxable, nondeductible payment.

(i) All sources of income available to either party, including income available to either party through investments of any asset held by that party.

(j) Any other factor necessary to do equity and justice between the parties.

“Dissolution of Marriage:” State terminology used in referring to divorce

Create your free account now.

*Major prenup hack alert!* We’ve created a “prenup encyclopedia” for your reference, because sometimes legal jargon is uh… confusing.

Waton v. Waton, 887 So. 2d 419 (Fla. 4th DCA 2004)

After living together for six months, former husband and wife decided to get married within the next 6 weeks. Former husband had been previously married and divorced and therefore insisted on a prenuptial agreement (also called an antenuptial agreement). The agreement stated that former husband was entitled to all property he owned prior to the marriage as well as “any hereinafter acquired, including any salary or income or dividends from such assets or interests.” The agreement also stated that former wife was solely entitled to all of her property which she currently owned as well as property she acquired after the marriage. Both parties waived their right to alimony. The former husband attached a list of his assets to the agreement with included approximate valuations (though some valuations were listed as unknown). The prenuptial agreement was completed two weeks prior to their wedding. Both parties were represented by separate attorneys.

The couple was married for 18 years. Upon dissolution, former wife attempted to set aside the prenuptial agreement based on duress, coercion, and overreaching. In deciding on the validity of the agreement, the appellate court conducted a two-step analysis. First, the court decided whether former husband made a full and fair disclosure of his net worth and income to former wife at the time of the antenuptial agreement. Second, the court analyzed whether the former wife entered into the contract freely and voluntarily.

The court ultimately decided that the evidence supported a finding that the agreement was valid based on the fact that the parties were both represented by counsel, the agreement was finalized two weeks prior to their wedding, and former husband disclosed his income and assets in the agreement. Even though some items in the list of assets attached to the agreement were listed as having unknown values, the court determined that the former husband was not attempting to conceal his assets from former wife and that the asset list gave former wife “such general and approximate knowledge of his property as to enable [the spouse] to reach an intelligent decision to enter into the agreement.” Del Vecchio v. Del Vecchio, 143 So. 2d 17, 21 (Fla. 1962). In reaching the ultimate decision, the court stated:

We recognize that the result in this dissolution after eighteen years of marriage is harsh. Wife has not worked full time in thirteen years, while Husband is now making a very large salary and has a net worth of over three million dollars. As a result, Husband is left with considerable wealth and income, while Wife waived all rights to alimony and equitable distribution by signing an antenuptial agreement. It is undisputed that the agreement is patently unreasonable. However, if an unreasonable agreement is freely entered into, it is enforceable.

Read the case here: Waton v. Waton

Flaherty v. Flaherty, 128 So. 3d 920 (Fla. 2d DCA 2013)

After living together for several years, former husband and wife got married. Around two months before the couple married, the former husband broached the topic of a prenuptial agreement for the first time. Former husband gave former wife a draft of the prenuptial agreement one month prior to the wedding and gave her a list of attorneys to consult regarding the agreement. Former wife first spoke with an attorney 11 days before the wedding. Upon this consultation, the attorney counseled former wife not to sign the agreement because it waived all of her rights to any interest in property acquired during the marriage as well as her right to alimony. The attorney told former wife that she would contact former husband’s counsel regarding the agreement. Former wife did not speak to her attorney again until after the wedding.

The next time she saw the prenuptial agreement was at 11:30pm the night before the wedding. Former husband instructed her to sign and notarize the agreement. The agreement was notarized at 2:00am the day the wedding. In the frenzy to complete the process prior to the wedding, former wife did not fully read the agreement prior to signing it. The finalized agreement was similar to the original draft except for two revisions allowing the wife limited alimony and a provision that former husband agreed to provide former wife with health insurance. When the former wife’s attorney received a copy of the agreement after the wedding (and after it had already been signed by former wife), she sent her a letter stating that the agreement remained unfavorable and inequitable. The former wife took no further action regarding the agreement.

Upon dissolution, the former wife sought to have the prenuptial agreement set aside based on duress. However, former husband argued that even if former wife signed the agreement under duress, she later ratified the agreement by not taking any action to modify the agreement or seek further assistance from her attorney. The trial court agreed with the former husband and declared the prenuptial agreement to be valid and binding on the parties.

On appeal, the appellate court reversed the trial court’s ruling and declared the prenuptial agreement to be invalid based on duress. Further, the appellate court determined that it was contrary to public policy to “validate a prenuptial agreement based upon a spouse’s failure to seek revision, amendment, or to set aside a prenuptial agreement during the parties’ marriage.” The proper analysis when the argument of duress is present, is for the party disputing duress to present evidence that the agreement was in fact, entered into freely and voluntarily.

Francavilla v. Francavilla, 969 So. 2d 522 (Fla. 4th DCA 2007)

This case emanated from a cycle of break-up and make-up between the parties that spanned several years and more than one divorce (read the full text for all the juicy details). Before getting married for a second time, the former husband insisted on a prenuptial agreement. The parties, both represented by counsel, spent several months negotiating the terms of the agreement. The former wife was aware of the former husband’s considerable net worth. The negations continued all the way up to an hour before the ceremony.

Upon separation, the former wife attempted to have the agreement set aside based on duress. The former wife argued that at the time she entered into the agreement she was seven months pregnant, her pregnancy forced her to leave her job as a flight attendant, and the agreement was not signed until one hour before the wedding. In analyzing the situation, the court stated, “[f]ocusing on the entire prenuptial negotiations, and not just on the endgame, leads to the conclusion that … there was no duress.” The factual scenario in this case lacked the time pressure aspects of some other cases (for example, where the prenuptial agreement is introduced for the first time shortly before the wedding) as the parties negotiated, while represented by counsel, for months. The court interestingly noted that the couple also married in a courthouse ceremony which could have been canceled much easier than if the couple had hundreds of wedding guests waiting along with the expense of a lavish wedding. So, the fact that the agreement was signed shortly before the ceremony is not the only factor considered by the court in determining whether a prenuptial agreement is entered into invalidly.

Aguilar v. Montero, 992 So. 2d 872 (Fla. 3d DCA 2008)

The parties in this case waived their right to alimony and specified in the prenuptial agreement that the waiver was effective as of the date that either party filed a petition for dissolution of marriage. However, the former wife sought temporary alimony during the period of time between the filing of the petition and the entry of a final judgment of dissolution. Based on the prenuptial agreement, the trial court denied the former wife’s request for alimony. However, on appeal, the appellate court reversed the decision of the trial court and declared that the former wife was entitled to temporary alimony (pre finalization of the divorce). In doing so, the appellate court reasoned that, “Florida law approving prenuptial agreements concerning post-dissolution support has so far not extended to provisions waiving the right to recover pre-judgment support such as temporary alimony.” The court definitely declared that pre-dissolution support cannot be waived.

Hahamovitch v. Hahamovitch, 174 So. 3d 983 (Fla. 2015)

In a prenuptial agreement, former wife waived rights to all of former husband’s solely owned property (acquired both prior and subsequent to the marriage). Upon dissolution, former wife argued that she was entitled to equitable distribution of the appreciation in value of husband’s solely owned property, which was not specifically addressed in the prenuptial agreement. The court found that the broad language of the prenuptial agreement excluding the parties from any and all interest in the solely owned property was sufficient to include enhancement in value and appreciation of the property, even that which is due to marital funds or labor, as non-marital property which was not subject to equitable distribution.

Lashkajani v. Lashkajani, 911 So. 2d 1154 (Fla. 2005)

Responding to a certified question of great public importance, the Florida Supreme Court ruled that a provision in a prenuptial agreement that authorizes recovery of fees (including attorney fees and court fees) by the prevailing party in lawsuit to enforce a prenuptial agreement is valid and enforceable. While a clause of this nature technically pertains to expenses incurred during the marriage, it is nonetheless valid because it is concerned more with distributing assets post-divorce than with pre-dissolution support (noting that Florida law has not yet extended freedom of waiver of post-dissolution support to waiver of pre-dissolution support). Additionally, the court also distinguished prevailing party clauses from support provisions in that they are intended to protect and indemnify a party who relies on the prenuptial agreement versus enriching the prevailing party. The court’s ruling was narrowly tailored to the issue of prevailing party clauses and did not address the validity of provisions under which a spouse has waived pre-dissolution support.